webmagazine Kamui Mintara

1986.05/Volume14 [Special Issue]

1986.05/Volume14 [Special Issue]

What foolishness my youth was spent in, and yet how single-minded and earnest I was. But I want everyone to know that even a little stone can sing.

My Life and Times by Miura Ayako

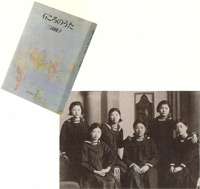

The writings of author Miura Ayako include a set of four autobiographical works. These are Kusa no uta (The song of the grass), Ishikoro no uta (The song of the stones), Michi ariki (There is a path), and Kono tsuchi no utsuwa wo mo (This earthen vessel too). The second volume of the set, Ishikoro no uta, opens with Ayako’s entering the Asahikawa Municipal Women’s High School in April 1935, and follows her life as she graduates from school to become an elementary school teacher who teaches her students to die for the emperor, and who, in every way, blindly submits to government propaganda until Japan loses the war. When she finally realizes that what she had been teaching her students was in error, Ayako falls into self-doubt and nihilism. The volume concludes in 1948 as she enters a prolonged period of medical treatment for tuberculosis.“What foolishness my youth was spent in, and yet how single-minded and earnest I was,”the author comments at the end of the fourth volume (written between 1972 and 1973) of the set, in reference to her youth as described in Ishikoro no uta. In this issue of Kamui Mintara, Miura Ayako discusses that part of her life and times, and what meaning they have for her now, with interspersed comments (in parentheses) by her husband Miura Mitsuyo.

Ayako (second from the right) with classmates in 1938.

Ishikoro no uta (The song of the stones) is an ordinary record of an ordinary woman as she enters high school, becomes a school teacher, and then finally experiences Japan’s defeat in the war. They say that the greatest hero cannot transcend the times he lives in. How much less can an ordinary person transcend the times? I was weak enough to be caught in the swirls and eddies of the age and got pushed far along with the flow. I was an ordinary girl who gradually became smeared by the taint of the militaristic era, until finally Japan’s defeat in the war threw me into doubt and despair. I decided I wanted to take a close look at this process. (p. 3.) [Unless otherwise indicated, all quotes are from Kadokawa Shoten’s 1974 edition of Ishikoro no uta.]

How naive I was back then. Of course I was only sixteen or seventeen when I first became a school teacher, so it would have been unnatural for me not to have been naive. Especially as I had been educated since grade school in the militaristic ideology, and as a young girl had no way of understanding or transcending the times I lived in. I understood nothing. Nothing.

So I just did as I was told.

A haphazard family of eleven

Let me start by describing my family at the time I entered high school in April, 1935. My father, Hotta Tetsuji was 45, and my mother Kisa was 40. I had three older brothers, an older sister, three younger brothers, and one younger sister. In other words, we were a large family, with eleven members in all. (p. 4)

I believe we were very poor. My father was chief of sales for a newspaper company, and received a salary of about 300 yen. According to my parents, that was a good salary. But my father was an eldest son, and my mother was an eldest daughter, so basically they had to support three separate households. During the years I attended high school, it was only the first time that I actually carried the money for tuition to school myself. Each time after that, my father would say “I’ll take it myself later,” which meant that he didn’t have the money, and he would have to take it to the accounting office past the deadline himself, or sometimes the school accountant would come to our home to collect it.

All the same, we were rich in spirit. My parents were very generous people. I remember times when my mother suddenly and quietly left the house while one of the relatives was visiting. My brothers told me they saw her enter a public pawnbroker to borrow money, and then pass that money wrapped in cloth to the relative.

Our home had definite views concerning children, and it didn’t involve the “raising” of them. For one thing there were just too many of us, and my parents were too busy to attempt it. My mother went with me to school the day I entered first grade, and after that she never once attended a school event, whether it be a school play or a graduation ceremony. Nor did she come for my high school entrance ceremony. You might say we were a free-spirited family, or maybe we were just haphazard.

My father was not a gentle man, at least not at home. He could flare up like a fireball, his impatience causing him to fly into rages. On the other hand, he was extremely fond of his children, becoming very distraught if any of us came down with fever or injury, and he would sometimes vent his anxiety over us by harshly scolding our mother. Worried that wiping the nose of a sniveling infant with the stiff paper we used in those days would irritate the child’s tender skin, he would actually use his own lips to clean the child’s nose. And though we frowned in distaste at the unsanitary act, we were inwardly moved by his gentleness. (pp. 5-6)

I bought a copy of Gone with the Wind after I became a school teacher, but my father insisted on reading it first. After he finished it, he scolded me saying, “You’ll be ruined if you read stuff like this.” During the years of my hospitalization, he would read the magazines I subscribed to and say, “I can’t let you read this kind of garbage.” He always read everything, and get angry with me afterwards. He insisted on his own way and he scolded frequently. But I loved him dearly.

My father, who was of average height and build, was a handsome man, and my mother was a beautiful woman. She always seemed to have a nursing child in her arms while trying frantically to keep up with the housework, but she never failed to be carefully dressed and neatly coifed. [...] She did not nag us or scold us children, but I think we actually feared her more than we did our father. (p. 6)

My mother was cheerful and fair-minded. (Mitsuyo: She always remembered the birthdays, wedding anniversaries, and death anniversaries of all the relatives.)When I was confined to bed because of illness, if I had friends in the same situation, my mother would pay them visits time and time again. But if I had to say which of my parents I felt closest to, I would have to say it was my father. He was so good to me that people actually described us by saying “He raises that child as though she were the child of someone to whom he owned a great deal.” He was a voracious reader of novels. Maybe that explains why we were so compatible.

I was very close to my older sister. I was not one to open my heart to even my best friend at school, but I could discuss my deepest feelings with my sister, and people often said of us that we “seemed like sisters who were meeting for the first time in a decade,” we always had so much to say to each other. I also had a grandmother who had the most forgiving heart, and I learned a great deal from her.

I think that a good environment is one in which people bring out the best in each other. In my life this role was played by my grandmother and my sister.

I wanted to become a loving teacher

Miura Ayako and husband Mitsuyo in their living room.

I looked through the train window at the coalmining town to which I had been assigned.This town, nestled in a valley between the hills, had one main road running through the middle of it, from which many smaller roads branched off to the right and to the left to climb up the hillsides. And along the sides of these hills, in orderly rows, each a step higher than the previous one, stood the kind of buildings they used to call “harmonica row-houses,” consisting of five connected living units to each row. It was a scene more abundant and vigorous than I had imagined. (p. 74)

As I approached high school graduation, I had no real professional goal in mind. I often went to what is now called Heiwa Avenue to send off soldiers departing for the war. One day I noticed some school children who had been brought by their teacher to see off the soldiers. I watched as they wrapped themselves around their teacher, trying to get her attention, and I thought, “Teaching seems like a nice profession.” A profession that required the exercise of love appealed to me, and I took the teacher certification exam while I was still a student. The school I ended up being assigned to was in the coal-mining town of Utashinai.

The school term began in April, and it was not exactly easy-going. For one thing, we were required to show up at school at an ungodly hour. This was because we were required to scour the inside of the building and the school grounds, and the teachers had to show up for work at 5:00 a.m. to manage it. It made sense to me that those entrusted with the education of children should discipline themselves by the cleaning and purifying of the school grounds. [...] The conviction that teaching was a sacred profession made me face this daybreak chore without suspicion. (p. 78)

I became a teacher at the end of what would now be called the first year of high school (10th grade). In those days the Sorachi district was considered an education paradise, and I had been assigned to the most vigorous of the schools in the area. I felt a deep sense of obligation and respect towards every one of my elders and teachers for the assignment.

“Let us adore the emperor and worship him!” the call would ring out, and the students would turn as one to face the framed photograph. “Respectful bow!” came the next command. As soon as the morning worship ritual was over, we led our students into their classrooms, [...] but unless they were exceptionally welltrained, the children would look around restlessly and their heads would not be still. They did not walk in regular rows. So, the all teachers were very strict. Even the women teachers dealt out corporal punishment without mercy. The system was thoroughly militaristic, but I was deeply moved by the earnestness with which students and instructors undertook education, thinking to myself that learning was meant to be carried out with just such orderliness and seriousness. (p. 79)

In those days we all had the militaristic spirit pounded into us, and we believed with utmost sincerity that we should fight to the very last man. (Mitsuyo: The emperor was god-man, and seeing him astride a white horse was enough to bring tears to our eyes. We believed until the very day of Japan’s defeat that Japan was God’s country. So it was unthinkable that we should lose the war. At the same time, a school principal was heard to say that “Life is precious and we should guard it carefully,” while others said in private that “Japan may be forced to an unconditional surrender.” But we had no ears to hear such words or eyes to see what was really going on. The voice of the minority was easily ignored. After all, in those days we feared to even say the innocent words “red dragonfly” because of the implications of the word “red.” If you had the label “red” applied to you in any way, it was enough to justify being pulled in for questioning by the authorities.)

At any rate, the people who abided by national policy were zealous for it. But if you were to disobey the national policy even one bit, you could be arrested. It wasn’t possible to buy books which would give you an idea of what was the right way for people to live. No one lent books to another with words like, “Take a look at this book.” No one ever talked about such things, and certainly not to me.

I was nothing more than a sixteen year-old girl who had no grasp of the time in Japan’s history in which I lived. (p. 79)

So it was much later that I finally learned what a dark age it was. It’s after you know the light that you recognize darkness. You cannot know darkness when you’re in the middle of it.

Tortured by meaninglessness

For seven years I put my heart and soul into teaching my students. I loved them from the bottom of my heart, and I would have been content to teach till I drew my last breath. But having to instruct the students to black out large portions of the textbooks we had used throughout the war years killed any desire I had to remain in the profession. (pp. 298-299)

We were convinced that it was a glorious thing to die for the emperor, and felt it a high honor to be in a profession that raised up the “emperor’s children” to believe the same. We bowed when we opened our textbooks, we make the students iron the pages if they became the least bit creased, and we had the students make dust covers to protect the books. After the defeat, we told our students to black out huge passages of those very textbooks with india ink. What made this exercise even more tragic was the fact that the students were so unaware of why they were being instructed to do this.

Teachers aren’t supposed to make mistakes. The students trusted us with a special trust, which is why this pain is so hard to express in words.

I even thought of becoming a beggar. No one heeds the words of a beggar enough to be influenced by them. I thought it would be best for me to be scorned till the day I died, that this was all I was worthy of. Having taught lies to my students, my sins were too great for me to be redeemed. I would never ever believe in anything again. Nor did I want to face the children again.

Having lost sight of what I should teach, I finally quit my job the following March [When I was diagnosed with tuberculosis] I felt like mocking myself by saying “it’s just what I deserve!” (pp. 300, 303-304)

The world I had believed in till then had been a world of lies. If you believe in lies, you naturally become empty.

I want you to know the times and the wretchedness of power games

In an upstairs study, Mitsuyo records as Ayako dictates for up to three hours each day.

What is a historical era? Does it come into its form just sort of naturally? I don’t believe for a minute that the era in which I grew up developed spontaneously. Those in positions of authority and those who manipulated them from the shadows-- they forcibly produced the tide which eventually swallowed up the common citizen. How many lives were lost because of it, and how many destinies went awry because of it? (postscript, p.314)

(Mitsuyo: After Ayako and I had traveled to various places around the world, it struck us quite forcibly that we must not allow this beautiful land of Japan, blessed as it is with pure waters and green hills, to slide into that era of darkness ever again.)

We feel quite keenly how precious are peace, democracy, and the freedom of speech. But we feel that the tide of the times is turning back once again. We live in anxiety lest our nation allow itself to return to those dark days we once knew. Not a day goes by that Mitsuyo and I do not discuss this serious concern.

I already sense that we are beginning to lose our freedom of speech. There are people trying to get the National Security Bill re-submitted to the Diet. We must not allow anyone to seal our lips. We must not for a moment take our eyes off issues that protect priceless life and peace.

I felt like a little stone that had been kicked into the gutter. My youth, as represented by that stone, was spent in foolishness and frivolity, yet it was single-minded and earnest. I am in many ways even now a little stone, but fortunately I came to know the Bible. And I came to know a particular passage in the Bible which goes, “Jesus answered, I tell you that if they keep quiet, the stones themselves will start shouting.”(Luke 19:40) I have marked this verse because I want all to know, that any otherwise insignificant stone can shout out. And because I want all to know the heartlessness of those people of power who try to crush such little stones as though they were bulldozers. (p. 312)

The Events Affecting Japan During Miura Ayako’s Youth:

In 1935 there was still a remnant of the unfettered thinking referred to as Taisho Era Democracy. The women’s high school in which Miura Ayako (born Hotta Ayako) was enrolled, was known as an enlightened school with a democratic spirit and active student government. Regulations that restricted skirt length, shoe style, and the singing of popular songs could actually be changed if the students protested. But along came the Manchurian Incident, followed by increased terrorism within Japan, and the prevailing cultural/literary trend became one of wallowing in the shocking and the bizarre. It was already a “dark ages” in which even sociopolitically aware students such as Ayako were prevented from realizing what was happening around them.

With the stir created in 1935 by the “Discourse on the Emperor as the Government Organ,” the 2.26 Incident that took place in 1936, and the “Japan-China Incident” (the Second Sino-Japanese War) the following year, Japan tumbled headlong into a militaristic era. A document known as the “Kokutai no Hongi” (Cardinal Principles of the National Entity of Japan) served as a textbook for educating citizens on the official teachings of the Japanese state. “We accepted with little resistance the apotheosis of the emperor and the propagandistic education that taught us that dying for the emperor was a high honor.”

The 7th Division was stationed in Asahikawa at the time, and a licensed quarter was established to serve its needs. The students would hear stories of escaped prostitutes found dead on the river bank after coughing up blood, and of Sano Fumiko, the anti-prostitution activist, bravely resuming her speech after having been attacked by sword. Many of the sick and wounded soldiers that Ayako and her fellow students visited in the army hospital had tuberculosis.

Ayako was sixteen in 1939, when she was assigned to teach at Kamoi Elementary School in the town of Utashinai. This cheery pastoral coalmining town was having a growth-spurt as a result of the war in China. The school was blessed with many teachers who had a passion for education, and the students loved their newly-assigned teacher. At the same time, life as a coal-miner was not an easy one. There was a large community of Koreans who had been dragged to Japan against their will as forced laborers, and who feared the Japanese as if they were devils. Meanwhile there were those, like the principal of the second school Ayako was assigned to, who murmured that “Democracy is best,” and coal-dust covered laborers who privately believed that “Everyone should be permitted an equal standard of living.”

As ideological pressure became extreme, those who did not cooperate with nationalistic propaganda came to be known as traitors of the state and they were hated. Most citizens had no access to the facts of the war and believed anything their government did was right. Ayako was no different.

A Brief Profile of Miura Ayako

“Not a day goes by that Mitsuyo and I do not discuss this serious concern”

Miura Ayako (neé Hotta Ayako) was born on April 25, 1922 in the city of Asahikawa. She graduated from the Asahikawa Municipal Women’s High School to begin teaching at the age of 16 in the coal-mining town of Utashinai. She was later reassigned to a school in Asahikawa city, but with Japan’s defeat in WWII, she was awakened to the errors of militaristic education and the adoration of the state, which led to her quit the profession after seven years of teaching. Almost immediately, she was diagnosed with tuberculosis, which spread from her lungs to her spine, confining her to bed for the next thirteen years. She received a Christian baptism at age thirty, and married Miura Mitsuyo when she was 37 (1959). In 1962, her essay “Taiyô wa futatabi bossezu” (The sun does not sink twice) was published in Shufunotomo magazine. In 1964, when Ayako was 42 years old, she won the Ten Million Yen Award from Asahi Shinbunsha for her novel Hyôten (Freezing Point), and was plummeted into fame. Until her death in 1999 she continued to write prolifically from her home in Asahikawa. Her most famous works include Hitsujigaoka (Shufunotomo), Tsumiki no hako (Asahi Shinbunsha) Sabaki no ie (Shueisha) Jiga no kôzu (Kobunsha), Shiokari tôge (Shinchosha), Hosokawa garacia fujin (Shufunotomo), Tenboku gen’ya (Asahi Shinbunsha), Deiryû chitai (Shinchosha), Hiroki Meiro (Shufunotomo), Hate tôki oka (Shueisha), Sen no Rikyû to sono tsuma tachi (Shufunotomo). In addition, she published a great number of essays and collected correspondence. Asahi Shinbunsha published the collected works of Miura Ayako in 1983. Miura’s works have been published in translation in many nations of the world. She died on October 12, 1999, at the age of 77.

Brief Profile of Miura Mitsuyo

“We must not allow this land to slide into that era of darkness ever again”

Mitsuyo was born in Tokyo on April 4, 1924. He graduated from Shotonbetsu Elementary School (Hokkaido) in 1939, and took employment with the Shotonbetsu Marutsû Transport Company upon graduation. In 1940 he began working for the Nakatonbetsu Forestry Office. In 1966 he retired from the Asahikawa Forestry Office in order to support Ayako’s writing career as her manager. He was baptized in 1949.

Kobayashi Takiji and his mother, as depicted by Miura Ayako

“It had never before occurred to me how frightening it could be to write a novel...

Who could have imagined that just writing a novel.... would get Takiji killed?”

Haha, written by Miura Ayako,

is available in hardback for 1,155 yen, and paperback for 483 yen.

Both versions are published by Kadokawa Shoten.

To be honest, I don’t really know much about Kobayashi Takiji.

And I’m quite ignorant about communist ideology. This being the case, I am rather puzzled as to why Mitsuyo should be so insistent on my writing a novel about Takiji’s mother.

(from the postscript of Haha, Kadokawa Shoten 1995:206)

The novelist Miura Ayako wrote Haha (Mother) in 1992, when she was in her declining years, at the age of 70. This was ten years after her husband Mitsuyo had first suggested the project. For a Christian writer, the act of writing is an evangelistic exercise. Thus, writing a novel about the mother of a famous communist was not something she could quickly or easily accept. But once she began collecting data for the book, she was amazed how a family burdened under such extreme poverty could have brimmed with so much kindness and cheer.

Seki, the mother of Kobayashi Takiji, was born in 1873 in Shakusonnai village of Akita Prefecture. She was married off to the Kobayashi family at age thirteen, mainly to lessen the number of mouths her parents had to feed. The man she married was a kind man, and they ended up having six children between them, including Takiji. All the children inherited their mother’s trusting nature, as well as her hardworking and considerate temperament.

The novel Haha covers the life of Seki from the time she was a child of four or five, until she was eighty-eight, in a simple conversational style. It is easy to imagine that the source of Kobayashi Takiji’s generous love for humanity can be found in the kind and gentle environment of this household. Another factor which deeply moved the author’s heart was the fact that the life of Takiji and the life of Christ share a common tragedy. Takiji was pulled in for questioning by the police and died at their hands, from wounds inflicted by something like a nail, before being returned to his mother. It brought to the author’s mind the tragic figure of Mary the mother of Jesus (as depicted in the Pieta), holding the lifeless body of her son against her breast after he was lowered from the cross onto which he had been nailed.

“I don’t know how the world reasons these things. But Takiji was such a loving boy, and so very poor, and I refuse to believe he was such a scoundrel that he deserved such a brutal death as that.” Was there no one who could judge the rightness and wrongness of what had taken place? It was this cry of Seki’s heart that motivated Ayako’s husband Mitsuyo’s interest and commitment to get her story told.

This novel is an invaluable work which throws into relief not only the character of Takiji, but those of his sweetheart Taki and other significant people in his life. Its depiction of Seki as an unschooled but steadfastly loving and faithful mother moved a great many readers in a way that was different from Miura’s other great works such as Hyôten (Freezing Point) and Shiokari tôge (Shiokari Pass). The novel was also made into a stage production.

The Otaru Municipal Museum of Literature has a large collection of Kobayashi Takiji-related documents as well as those connected with his mother Seki on display. Among the items on display is a portrait of Seki and the famous poem “Ah, February is here again” which expresses a mother’s deep sorrow-- a sorrow which had not healed even thirty years after Takiji’s death.

related website: http://www4.ocn.ne.jp/~otarubun/

Webmagazine Kamui Mintara brings you the culture and customs of Hokkaido

Kamui Mintara is a bi-monthly magazine which Rinyu Corporation published from January 1984 to January 2004 to bring readers the culture and customs of Hokkaido. Beginning with Issue 2:1 (121st issue) the magazine became available to the general public on the internet as “Webmagazine Kamui Mintara” in the hope of reaching a wider audience, and encourage two-way communication between the publisher and the readers.

Back issues of Kamui Mintara through the 120th issue, special editions, and essays are available in our internet archives in html format.

We offer an on-demand service to permit easy searches through our archives.

● This brochure has been translated from the Japanese original by Deborah Davidson

● Contact Kamui Mintara editor at Rinyu Corporation, Kita 9-jo, Higashi 2-chome, Higashi-ku, Sapporo 060-8582, Hokkaido, Japan

email:kamuimintara@rinyu.co.jp

tel:+81-11-742-4233 fax:+81-11-731-1456